The Invisible Gorilla

How we can overlook things that are right under our noses.

How often do we miss things that are seemingly right under our noses?

On the commute home from work today, I found my gaze drawn towards a woman in a bright, vibrant, pink outfit. Aside from the fact that I love this colour (the gerbera colour that mum would have called ‘cerise’), I found myself admiring this stranger for her apparent pride in wearing such a stand-out colour. I pointed this out to my daughter who said, ‘but mum don’t you think her tattoos are more amazing? The ones on her face?’ The moment she mentioned it, I did see the tattoos, which were indeed amazing. The point, of course, is that I failed to see something glaringly obvious because I was focused on something else.

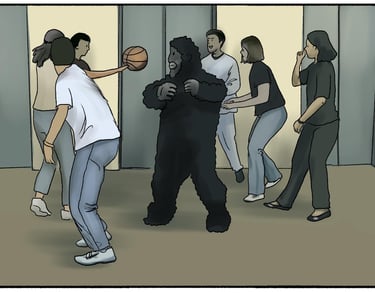

The selectivity of human attentiveness is not a new concept in psychology. Made famous in their ‘invisible gorilla experiment’ Chabris and Simons demonstrated how many people notice only what they are focusing on. A sample of students were asked to watch a video of two groups of people playing basket ball. They were told to count how many passes a team made. Whilst many of the respondents correctly counted the number of passes, what they failed to notice was a person in a gorilla suit, who walked through the game, pausing in the centre of the game to beat her chest.

The experiment has been repeated to find the same result by other researchers, and a quick google search will afford access to various You tube videos of similar scenarios. The video (or similar) is used on lots of management and self-development courses and it has surprising relevance to our everyday lives.

Often, clients in therapy talk about patterns (of which they may or may not be aware). It might be that they feel that everybody around them doesn’t value them. They will most likely be able to illustrate this idea with lots of examples of family members or work colleagues taking them for granted or not considering their needs. And in some of these situations (but not all), it may be likely that their feelings of injustice are justified. And so, this is what they have come to expect: people overlooking them. And the more they look, the more they will find examples of this in their day to day life, thus perpetuating this idea and making it more deeply ingrained. They might even (unknowingly) develop a role of victim or martyr.

Life often seems to manifest what we are looking for, as illustrated by Rhonda Byrne in The Secret. If you look for a green feather for long enough, you’re likely to find one. I found one (well actually lots) during the Manchester Marathon, being worn by a runner in a parrot suit, who beat me by about 10 minutes (how irritating).

Green feathers aside, what these clients are not looking for, however is examples of the opposite: people treating them with consideration or showing love. A person sitting next to you when you are sad but not saying anything isn’t necessarily ignoring you; it may just be that they can see you suffering but don’t know exactly what to say, so they stay close just to show you they they’re there. Something as small and seemingly insignificant as a person offering you a cup of tea could be an act of care.

My own daughter, always just before bedtime (the time of day when I’m the most cranky and just want to settle down) often asks me if I will ‘finish’ straightening her hair. When I go into her room and pick up the straightening irons, I realise that her hair is already pretty straight. It struck me that what she really wants is just my company, but as she’s a teenager, she doesn’t really know how to articulate this. Or perhaps she feels embarrassed. It doesn’t matter. Essentially, it comes from a loving place and shows that I’m valued. I could easily focus on how long my day has been, and how I need to relax before my next long day which looms ahead of me, and if I dwell too long on it, that’s all I will see. But if I can move beyond this, I can see another truth, which is much more useful for my state of mind.

Of course, seeing beyond what you expect to see is not necessarily so easy. It can be a little like finding Wally. And sometimes, people need a little external help with this, which is how they find themselves in the counselling room. It’s much easier for an outsider to spot the ways in which we can trap ourselves in an unhelpful narrative. But once we have self-awareness, we can work with this.

So next time you’re thinking about a pattern, ask yourself what you might be missing. Some face tattoos or a dancing gorilla? Or just maybe something that might shift your perspective just a smidge. And that smidge can make all the difference to your wellbeing.